Blog 29: Collector’s Corner

Recently, a friend was telling me about her mother’s dementia, a dementia known as Frontal Lobe Dementia. This dementia, my friend said, has turned her mother into a chronic and compulsive hoarder. Every table top and spare space in the mother’s house, she told me, is covered with neat piles of things like empty Premium Leg Ham packets, margarine containers and jam jars (all washed), bags of knitting wool (for knitting “squares” for the church), newspapers (bundled on chairs), Lions’ Club Christmas cakes (stacked in the bath), books, magazines, cleaning rags, plastic flowers, and so on, and so on. My friend said that her mother had always been a “saver” but that, before dementia, the things saved had never been allowed to overrun the house. Now, though, it was getting so out-of-hand, that the children had to hire a skip every six months to take the piles away so that their mother had room to start again.

Bill, with his different condition of Vascular Dementia, was not like that. He was more of a “collector” than a “hoarder”. All his life, for example, he had collected magazines. National Geographic, Wooden Boat, Classic Boat, and Woodworking magazines had always adorned various shelves in our houses. And, when he ran out of shelves, Bill would just turn around and build himself more. He was an expert at it. He never thought of throwing any of his magazines out. He just built more shelves for them.

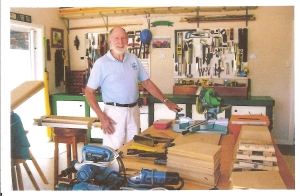

As well as magazines, Bill collected useful off-cuts of timber, nuts and bolts and screws, hose parts and leftover paint in paint tins. He had, also, an impressive collection of shells, which he had gathered when he was working in Milne Bay in the late 1960s, a collection of carved walking sticks, and a workshop lined with tools, some very old and others quite new.

Now, this collecting, that Bill did, was probably no different to the collecting done by most men of Bill’s age who own a shed. For men of Bill’s generation, those born in or around 1939, the urge to collect was often spurred on by the fact that they were World War II babies, reared mostly in poor conditions.

Everything that they had or they ate in their young years was either homemade or home grown, even the soap that they washed with and the butter that they spread on their slices of damper.

Look at this photo of Bill, with his mother and brother, taken about 1946:

All items of clothing worn by these three pictured above, except for the shoes, were made by Bill’s mother. And his father and grandfather built the building that serves as background for the photo. People of that generation worked hard to make enough money to pay for materials. There was never anything left over to pay for the making. They had to do it all themselves. Little wonder that they saved off-cuts and useful bits and pieces that might save them a penny or two.

With the onset of dementia, however, Bill’s attitude to his collecting changed. He became more possessive and more protective of his “stuff”. Whereas, in 1995, when we first moved into our present abode, he was most willing to lend a young neighbour his tools, by 2010, visitors were not even allowed to touch them. And it could be embarrassing when he would admonish a friend, who had picked up a hammer from his workbench, with:

“Put that down! You can’t touch that! That’s mine!”

And, when families with children came to stay, the cabinet housing his collection of shells had to be wrapped in tablecloths to ensure that the shells were neither touched nor looked at by the children. Previously, as well, when our son had wanted to borrow a magazine, it was loaned freely. But, after dementia took its hold, the magazine had to be sneaked out behind Bill’s back.

During 2010, this tendency to hang on to his possessions and to guard them against others, led to Bill hiding his goods in the boot of the car, e.g., the photo frames that we have already talked about. At any one time you might find there, in that car boot, three ornate, timber jewellery boxes, full of his collection of badges, shirts from his dressing room (was he planning to go to Sydney, I wondered?), magazines, some tools, the washing basket, the bucket of pegs, the photo frames and a container full of Lego. The Lego was there because a friend, who worked in aged care, had said to me that Bill might build with it. But Bill, by this time, was way beyond building with it. Instead, he would pour it, from the Lego container into the washing basket, and back again. Or he would store it, as he did when he hid it in the boot of the car.

By far, the most disturbing aspect of this behaviour, for me, occurred when Bill decided to hide the mail every day. If it went into the boot of the car, I would think:

“Good! I’ll get it when he goes to sleep.”

But, if it went into his pocket, I was often not able to retrieve it easily because of the way that he sat in his chair when he slept. And sometimes I wouldn’t be able to find it at all. He would have taken it out of his pocket some time during the day, when I wasn’t looking, and hidden it in some other hiding place, not the boot of the car.

The same thing could happen if I was working on the computer while he was awake. Invariably, while I was working, he would come and stand beside me and “tidy up” my desk. As I worked, the electricity bill might go into his pocket, not to be seen again for some time, or a scrap of paper, important to me, might disappear, or even my pens might go. One day, panic stations, even my address book went missing.

Mostly, things were found, eventually, in some obscure spot like Bill’s underwear drawer. But, sometimes, when I found them, as happened with the address book, I would realise that he hadn’t taken them at all …… that I had hidden them to prevent him from getting them and forgotten that I had hidden them and where.

…………………………………

They say that carers of dementia sufferers often end up with dementia themselves. Sometimes I would think, as I tried, in vain, to race Bill to the mailbox, that that was the way that I was going. Such is life when you live in a mad house.

Fay

The photo of Bill in his workshop was taken in 2009 when he helped a friend build wooden collection boxes for our Rotary Club. The boxes were placed in Chemist shops for the use of people returning Bowel Scan testing kits.

I returned one such kit today (15/06/2013) and was delighted to see that Bill’s boxes are still being used.

Bill’s box-building friend has commented to me that he detected no sign of dementia in Bill over the weeks that they were building those boxes but I do remember that that friend had to make a template for Bill to work from because he could no longer measure and he remembers that Bill was experiencing a lot of problems with language.

Harold and Nola

Hi Fay,

As we said previously, it needed a strong soul to go through this, make notes on where the journey you were being forced to take as the illness progressed, and now be able to go back over it in an effort to help others. And never mind about the madness, in one way or another we are all alittle mad at times – no, let’s make that most of the time.

Love, Nola and Hal.